It must've been a wonder when it was brand new

Music and books from France, Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Auckland, Chicago, London, Rio, Monterey, Kingston, Switzerland and more ...

Reasons to be careful, part 1

Travel has an odd aftermath: you are immersed in the moment, and the moment often feels life-changing, but in an instant, it’s gone. I’ve just spent a month in Western Europe, mainly France and Portugal, and that feeling of a life-changing moment occurred a few times. Neither country is new to me – I’ve been to Portugal about eight times and France probably 30 times in the last decade – and that moment eluded me in Portugal this time, unlike the last time I was there in 2019. Then, we genuinely believed we could live in Lisboa and nearly made an offer for a place just west of the centre.

Fortunately, COVID intervened, and we backed off. Now, the riversides and blocks within a kilometre of the river heading north are swamped with flag-following tour groups and bad pizza (in the centre) and vast swarms of digital natives who seem to party until dawn in the streets by the river and then overflow cafes during the day, also at volume. Add to that, thousands of middle-aged American couples loudly projecting in restaurants as they (understandably) try to find a new life beyond Trumpland.

My escape in Lisboa this time was to walk north, or use the metro if it was too hot, away from the swarms, into lovely everyday Lisboa beyond the scrum. As is my way, I circle good coffee and ensure it’s near one or two record shops. Lisbon boasts some wonderful record shops. Not the handful downtown, which are either stock-barren, overpriced or disinterested; or a mix of all three. Rather shops like Flur, a neat curated store of eclectic music, which, for better or worse, made The Financial Times’ somewhat peculiar list of the best record stores in the world last year. Much of that list is better ignored, but Flur definitely deserves its place.

Last time I was there, it was uncomfortably located by the river in an anonymous new strip-mall near the cruise ship terminal, accessible only via a large concrete plaza without any shade from the often harrowing Lisboa sunshine. It’s moved – now to a suburban market northwest of downtown, next to a Metro station in a Digital Native/tour-group free ‘burb full of other interesting shops. Perfect. What’s even more perfect is that it’s just a few hundred metres from the city’s other great record shop, Tabatô, a den of equally eclectic jazz, plus bins of South and Central American pop, soul and grooves, reggae and African music, all at prices that seem to ignore the often eyewatering price tags on MPB and similar global genres in the international collectors’ market. Yes, I bought records: an Ornette Coleman and John Cale’s Academy In Peril (see below) at Flur and Milton Nascimento’s self-titled 1970 4th album and a quirky, unknown Brazilian pop duo at Tabatô (again below).

The reaction when I showed B my scores was a big frown. I had sworn I wouldn’t buy any records in Portugal, given EasyJet’s baggage mafia rackets, and I had already bought four records in beautiful Coimbra. Yet, Brazilian music (a current obsession) and Portugal somehow go together. “You can go nuts in Paris” (I did), so I mailed the records from Brazil (mostly) I’d purchased in Portugal to a friend in the 7ème in Paris. We won’t mention Porto.

Which brings me to Laurent Garnier. Almost.

The current plan (or at least, possibly) is to buy a semi-rural— but not too rural— (I’m a city soul)— largish house somewhere in the southwest or south of France as a home base. The idea is to gather the things we love, which are currently scattered all over the planet, to create a space we can call home—full of the physical things that help define us. For me, that’s mostly books and vinyl records. Which really brings me to Laurent Garnier.

Central to the perfectly-formed 2021 feature-length doco on the very-famed French DJ is his record collection. Or, at least, Laurent relocating his large collection (which was around 60,000 records in 2015) to a new home, though not far from his previous residence. He achieved this with a team of friends, a large articulated trailer, and a tractor. Throughout the movie (which was filled with other parts of his story and words from his peers), we saw shots of Laurent with his collection (below), Laurent packing his records, Laurent loading his records onto the trailer, Laurent on his tractor (below), Laurent driving his tractor with the trailer through the French countryside, and finally Laurent arriving at his new home.

Watch the movie if you can, but the main point of all this is the decision I will face soon. I don’t have 60,000 records, but I might have 20,000, split roughly equally between Asia and a storage unit in Auckland. We won’t discuss books.

Of course, I could sell the whole lot, but I clearly won’t; I’d rather sell my aged soul at the next crossroads (perhaps I already have, crossing any road in Bangkok feels like a trip to hell). Alternatively, I could sell some selectively; however, the time involved in doing so is daunting, and Auckland or Bangkok don’t seem like the best places to undertake such a task. I could open a shop with 5000 records, but again, lifestyle and geography suggest that Auckland isn’t the ideal location for this. Perhaps I am faced with a tractor.

Reasons to be cheerful, part 2

Twelve records…

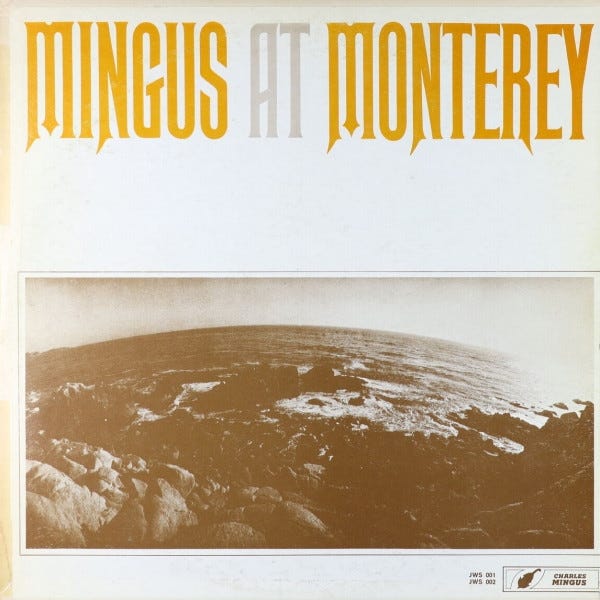

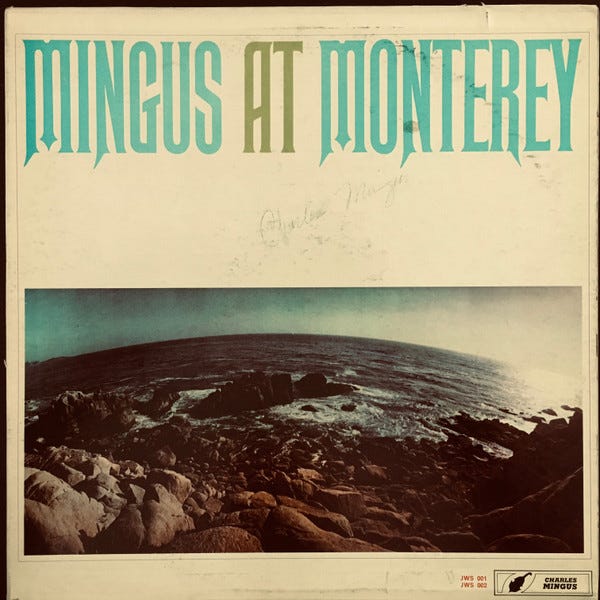

Charles Mingus – Mingus At Monterey (Charles Mingus, 1965)

The Mingus discography is vast and challenging, much as Mingus was as a man. It also sways all over the place, and while nothing is ever bad as such (or really much less than great), there are peaks and even higher peaks. 1964 was one of Charlie’s highest peaks. Having gifted the world The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady in 1963, the year itself offered up the majestic solo Mingus Plays Piano (recorded in 1963), and one of his most important albums, Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus. There were live albums featuring Eric Dolphy, including Town Hall Concert and Cornell 1964 (the latter was not released until 2007).

Then there was Mingus At Monterey, recorded at the 7th Monterey Jazz Festival on 20 September 1964, by the festival promoter Jimmy Lyons and possibly RCA engineer Bob Simpson (in the recording, Mingus says he has no idea it’s being recorded). The tapes were then gifted to Mingus, and here’s where the story gets interesting. The remarkable small band (Lonnie Hillyer, Charles McPherson, John Handy, Jaki Byard, Mingus, and Dannie Richmond) was fresh from a European tour and was allowed to run over their allocated time. Without a record label, Mingus took the tapes to RCA’s studio in New York, where he mixed, edited and compiled the release. It’s unclear exactly when this was released. Billboard, announcing the 1965 festival, which coincided with the UCLA date, notes that this album was already out. In April 1965, the same magazine also says, “Mingus, a brilliantly unpredictable musician, entered the disk business by offering an LP of his 1964 Monterey performance via mail-order.”

Mingus was, despite the tour, broke. He was out of contract with Impulse and decided to release the tapes through his label, Jazz Workshop (although the only branding is for ‘Charles Mingus’), which was originally founded in 1957 but had been dormant for several years (it also served as his music publishing entity). To maximise returns, the initial copies were sold solely via mail-order. And so it was, at least initially. In late 1964 or early 1965, Charles made the recordings available exclusively by mail order from Charles Mingus Enterprises Inc. in NYC. He promoted it with an order form, which came with Mingus matches given away at gigs. It’s unclear exactly how many were pressed, but online speculation suggests between 500 and 1000. It was initially packaged in a single-pocket sleeve with a sepia-toned image. Later, though it's unknown exactly when, but likely in 1966, a revised edition introduced a gatefold sleeve and a colour version of the image.

This was the only way you could buy the set until 1968, when, driven by financial stress (as stated in a letter from Charlie that appeared in the first copies of the reissue), Mingus licensed it to the tender mercies of Saul Zaentz of Fantasy Records, whom he describes as “an honest person” (one suspects John Fogarty might grimace at that description). As a Fantasy release, it was distributed worldwide, with the first batch using those original RCA Hollywood masters that first arrived in early 1965, albeit increasingly worn out. At the same time, the cover was changed to a full colour image.

Somehow, though, the original tapes somehow vanished. One story circulating is that Capitol discarded them during vault clean-outs in the early ‘70s, but that raises more questions than necessary and is likely false (it was transferred over the years from the 1965 mail-order release mastered at Capitol). Either way, they were lost, meaning every pressing after 1968, whether on vinyl or CD, was sourced from second or worse generation vinyl rips. The audio quality on all releases from 1969 to 2024 has been notably flat, often dreadful, making the original mail-order first edition the benchmark. The French semi-legit pressing on the dubious America Records, like many of their releases, is best avoided.

I have a decent 1981 Japanese pressing, and it was that version which upended my world for about a week or ten days when I first found it secondhand a couple of decades ago. That was when the three-minute bass solo that opens the 23-minute Duke Ellington medley blew my mind. Or it did until I stumbled upon a flawless copy of the 1965 single sleeve mail-order original in a jazz bin in Bangkok earlier this year. Goldmine tells me that it’s worth US$700 as near-mint (which mine seems to be), which also blew my mind a little. However, Discogs has what seems to be a copy listed at Very Good Plus, but described as “vinyl shows surface wear” in a typical Discogs very optimistic grading, going for $200. I paid around $50 (yes, that’s a record collector brag).

I’ve not heard the 2025 Record Store Day version, which claims on the sleeve to have discovered some missing tapes in Mingus’ archives after more than 55 years, nor read anything that verifies that claim. However, I doubt it compares to this original 1965 mono RCA Custom low-number pressing. (The album has always been in mono, even though it has been incorrectly marked as ‘balanced stereo’ over the years.)

Sadly, the Spotify and Apple versions appear to be sourced from muddy, unknown generations – or are they the RSD ‘remaster’? The copyright says yes. Strange again.

Either way (and it matters not, since I fell in love with a vinyl-drop pressing), this is the man whom Ralph Gleason once said, “Mingus erased the memory of any bass player in jazz.” This is also a bassist who openly stood on the shoulders of his idols, with Duke Ellington being one. 1962’s Money Jungle, in which Mingus and Max Roach coaxed Ellington into contemporary settings, is defined by the reverence the duo show towards the great man (despite Duke having fired Charlie in 1953, when his fiery temper clashed with others in the band), and this reverence, perhaps even adoration, opens this set, with an emotive small band tribute to Sir Duke that peaks with a lively and combative ‘Take The ‘A’ Train’, a tune he recorded a few times (notably on 1961’s Pre-Bird).

“I imagine I should say, “I love you, madly” at this point.”

That’s followed by his sublime signature ‘Orange Is The Colour Of Her Dress’. The crowd was all on their feet now, or so reviews said. Mingus describes it as ‘turbulent.’

However, it’s the final track, the politically charged ‘Meditations On Integration’, that marks Mingus At Monterey as one of the peaks in a career with around fifty albums. Played here for the first time, Meditations arrived two months after the passage of the US Civil Rights Act and three months after Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney were killed by a Ku Klux Klan mob near Meridian, Mississippi.

The small band from the earlier tracks grows into a big band, strengthened by seven horns, and they create what Mingus described as “a prayer of peace, a prayer of love … a prayer from inside, from finding my torment and my problems in this society”.

They create an extraordinary journey that fits equally within the European classical tradition of the early to mid-20th century (because “black people aren’t expected to play classical”) as it does with blues, gospel, and the big bands of Ellington and Basie that Mingus was steeped in. The 24 minutes shimmer, soar, clash, and finally explode to the first standing ovation in the festival’s history.

“I felt like I was playing to god.”

The missing tapes and messy legal situation with Fantasy after Mingus’ death meant that by 1982, this was out of print, although a tentative and soon withdrawn US CD appeared in the late 80s. The album faded from view, as did Mingus in much of the world.

But not entirely: nearly two decades later, in the 1980s, ‘Meditations’ was the music The Rolling Stones played loudly and in full in auditoriums and stadiums before they appeared on stage (Thanks to Charlie Watts, one assumes).

And of course, the Japanese never let it go out of print.

A 1968 Mingus doco, although not really for your pleasure. It’s not easy viewing:

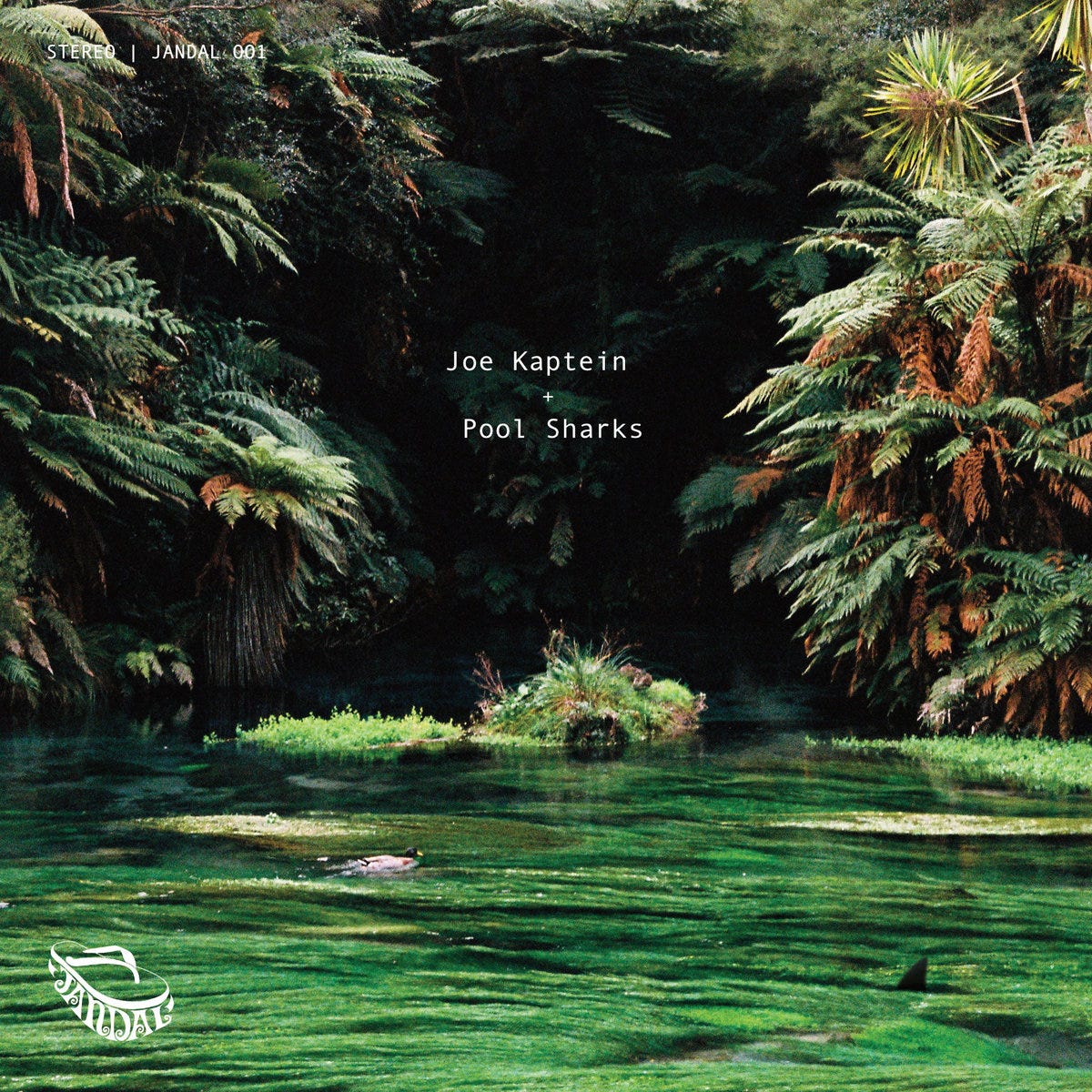

Joe Kaptein + Pool Sharks (Jandal, 2025)

A friend and I were talking about the evolution of a New Zealand jazz sound over the decades, and we both agreed it’s a thing, although a thing that’s very hard to nail down. Just as the UK, Germany, Jamaica, South Africa, Scandinavia, Japan, Brazil, and other nations have slowly (some not quite so slowly) evolved a unique feel (rather than a sound) for the jazz created within their borders or made by people raised within their borders, you can almost touch the contemporary Aotearoa jazz feel.

If you want to put a name to the origins, it’s likely a man who came from unlikely musical beginnings, Mike Nock, whose first recordings were with early rock’n’rollers, and he toured with Johnny ‘Pie Cart Rock’n’Roll’ Cooper. Nock left New Zealand in the early 1960s and never returned to the country to live, but the music he made cast a very strong and very positive shadow over the music being made locally, as did his successes (Miles famously called Mike one day and started the conversation with, “They tell me you’re a genius”) and the often inspirational catalogue of recordings he led over the next five decades. Records like Ondas (ECM), the three Fourth Way albums recorded for Capitol in LA, and the spacious, almost-jazz-rock, Between Or Beyond, by the Mike Nock Underground, released on the German MPS label from 1971, which I adore.

Then we have the music created by Murray McNabb, often with Frank Gibson: not only the jazz-rock Dr Tree, which feels more widescreen and Pacific than their UK and European contemporaries, and less oppressive than much US jazz-rock, but also a series of South Pacific jazz recordings over the decades. There’s Dave Macrae and Joy Yates’ Pacific Eardrum trilogy, and Nathan Haines, Mark de Clive Lowe, The New Loungehead, and Jonathan Crayford, who are just a selection (though a strong one) of musicians and bandleaders who have, consciously or perhaps unconsciously, laid the foundations of Pacific Jazz. This fabulous nine minutes from 2019 is just one example:

Mike Nock’s own stylistic foundation was the radio show he was addicted to as a teen, Arthur “Turntable” Pearce on 2YA. As he told writer Norman Meehan, “He would play the latest music from the US, it wasn’t all jazz, but it was comprehensive. There were little groups all over New Zealand that would study this show and get together and talk about it.”

This brings me to 2025, and we are well into a decade, or perhaps two, of music that reemphasises our “feel”. As in other countries, this has evolved – modern UK jazz has absorbed decades of dub, reggae, hip-hop, DJ culture, and more, pushing it to a stage where it stands as one of the defining regions of the global genre. In New Zealand, forty years of Pacifika and South Pacific roots music have elevated our music and jazz to a level that Mike Nock or Murray McNabb, despite their significant influence, could not have imagined in the 1970s.

For all that, as much as Joe Kaptein’s new album evokes Nock’s Between Or Beyond to me (or at least it does in parts), it’s probably more about the South Pacific spaciousness of the jazz we make. Jazz is essentially urban music, but urban has different meanings in various places. In the US East, it reflects the sound of gritty, congested city centres created initially by the racial underclass to express their lives and struggles; in the West, urban spaces are more open, and the jazz from there seemed to reflect that space. UK jazz was derivative in its early years, but it came of age in the late 1960s when it embraced the more structured European musical traditions, broadening its sound. This sound then evolved with the overwhelming influence of the Windrush generation, their offspring and other post-Empire absorptions. Japanese jazz is characterised by clarity, precision, and often delicate beauty.

New Zealand hardly has urban centres, at least as they’re recognised by much of the world. Our cities are expansive, generous in the space given to each human, and relatively unhurried places, bathed in South Pacific sunshine for much of the year, and are filled with the sounds of soulful Pasifika and waiata.

I’m ranting, but over the last decade, we’ve created a body of work that includes the assorted recordings by Julien Dyne (not least The Circling Sun), Lucien Johnson, Avantdale Bowling Club, Mara TK, and Myele Manzanza, and, across the Tasman, Menagerie (driven by West Auckland kid Lance Ferguson), all of which feel distinctly ours in the same way Brazilian jazz has that uniftying something regardless of stylistic differences. I’m just thinking out loud.

Of course, my argument is tossed in the air in places. A track like Joe’s ‘Herb Albert’ evokes the US West Coast, but even then, there’s a tenuous connection to New Zealand. Herb’s 1965 album Whipped Cream & Other Delights literally defines charity shops in Aotearoa and remains one of the biggest-selling albums in the country’s history. However, Joe’s ‘Herb Albert’ seems to reference Herb’s work from the 70s and early 80s, which became notably funky and dancefloor-friendly. I like this one and this one:

Which sound nothing like Joe’s ‘Herb Alpert’ of course.

I’ve not really talked about Joe’s record, it seems. I should, but this is now too long. Unlike this wonderfully eccentric album, which seems to successfully wander across the spectrum of sounds that we can and perhaps should call Pacifika jazz. I love this gorgeous epic, which I suspect both Mike Nock and Murray McNabb would nod very approvingly to:

Dave Holland + Sam Rivers (Improvising Artists, 1976)

There’s a recent Amoeba What’s In My Bag? video on YouTube featuring Don Was, the multi-tasking creative who now heads Blue Note Records. If you haven’t seen these, a musician or music name is allowed to wander through the massive LA record store and select a handful of records they want to take home. They explain why. The series is hit-and-miss, partly because the selector’s taste might not excite, but also partly because, despite its size and reputation, Amoeba is, like many large shops, patchy as a record store. It’s mostly filled with nearly everything you can find anywhere, rather than the curated selection available elsewhere, but it misses the passionately selected niche wonders found in smaller shops. It’s a bit like Kentucky Fried Vinyl. Wearing a backwards baseball cap and hunting for Dark Side Of The Moon on pink vinyl.

One of the records Don chooses is Wayne Shorter’s Speak No Evil, and he praises the 1966 album as the finest record in the Blue Note catalogue. It’s a bold claim, but I suppose he’s the boss, and few would argue it’s well up there.

While I’m cautious about being that absolute, I feel much the same about Sam Rivers’ 1965 solo debut, Fuchsia Swing Song, the first of a towering trilogy for the label.

Despite that, saxophonist Rivers is forever doomed to be cast as a second-tier jazzman. His catalogue from the 60s to the 2000s is almost without equal, but as Chris Kelsey writes on AllMusic, “he sometimes had an unremitting seriousness that could be extremely demanding, even off-putting.” He was also deemed difficult, not only as a musician but also as a prickly individual who knew what he wanted. That may partly explain why he frequently changed labels. Increasingly, the history of 20th-century jazz is being written by a small number of record companies. A handful of players sit above it all (Miles, Coltrane, Monk, Evans and Mingus mainly), but the legacy of the century that doesn’t rest with those five is being written by Universal (Verve, Impulse and Blue Note), Sony (Columbia, RCA), and Concord (Fantasy, Prestige, Milestone and Contemporary) through their successful, aggressive reissue programmes. UMG, in particular, operates a vast network of websites under various brands, selling jazz worldwide, all managed by the Verve Label Group in LA. The companies mainly press in Europe and sell everywhere around the world as a domestic market. And it’s their catalogue that fills bins, websites, and social media as jazz’s history. That defines jazz to ongoing generations.

The reality is that much of the most intriguing jazz—the eclectic, boundary-pushing records—was often released by small, independent labels, produced in limited quantities, and then fell into obscurity. Sam was too difficult for the major labels, which ultimately forced him to release his music through a succession of independent labels. Or maybe that freedom is the way he wanted it.

Bassist Dave Holland said, correctly, some years ago: “There are countless musicians who do amazing things that never rise to the status that you and I may think they deserve. It’s just the way the business works. It may be they chose a path that was more unique and more challenging.”

Which brings me to this remarkable record. Two sides, two tracks, two musicians, and two instruments (three if you count tenor and soprano saxophone separately), and nobody else, recorded for Paul Bley’s niche-defining avant-garde Improvising Artists Inc. label (the previous albums were for Italian indies, Red Records and Black Saint).

Briton Holland has an impressive CV, which, of course, includes In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, and at the time of writing, he’s still performing and recording.

The self-titled record, recorded in a single session by Bley on 18 February 1976, captures these two incredibly articulate musicians improvising playfully over and around each other. The recording is so clear that you can hear Dave’s fingers touching the strings, pulling the session along as Sam melodically darts around him. It needs nothing else.

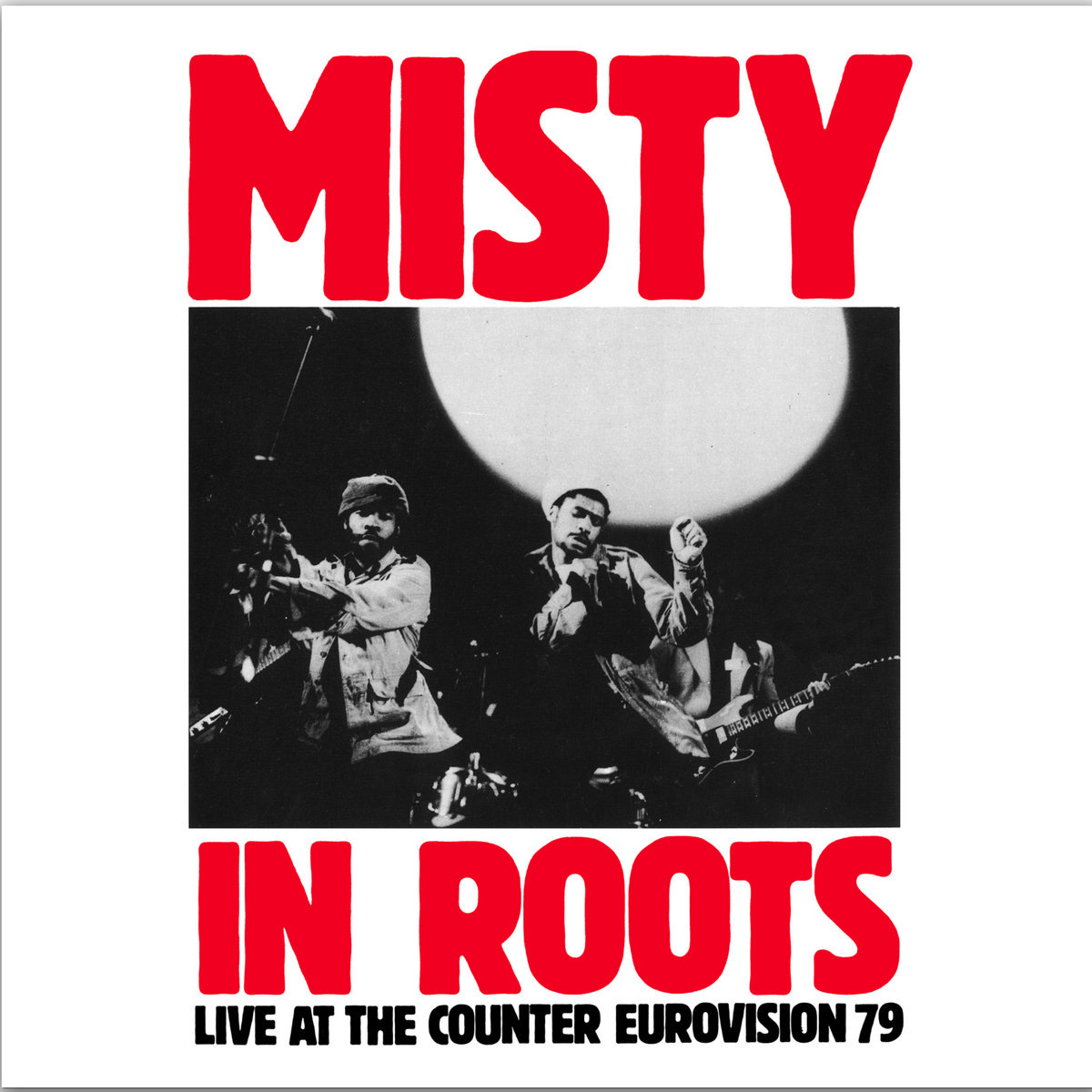

Misty In Roots – Live At The Counter Eurovision 79 (People Unit, 1979)

Every single second, still.

A record that has been called one of the greatest live albums more than once, I purchased this in 1980 from my friend Tony Peake at the University Bookshop in Christchurch. (At least I assume it was 1980; the exact date of release is difficult to determine from afar. John Peel played ‘Oh Wicked Man’ in December 1979; however, it wasn’t reviewed in the important UK monthly Black Music and Jazz Review until November 1980.)

In those straitened days, reggae that wasn’t released on Island or Virgin’s Front Line often didn’t reach our NZ record shops. UBS was the exception, and what an exception it was. Tony would call me now and then with things he thought I needed. This was one of those. I’d often send him cash through the mail. Over the next decade or two, this album was a constant, beloved companion. It was my go-to when I’d had a rough day, and also when I wanted to celebrate. I suppose most people have something like that, and this live-recorded (in Belgium) dawn of UK roots reggae was mine. The recording: I love the elastic, precise and groove-shaking snare (Julian Peters), the dense, melodic organ which leaps out of the grooves (Vernon Hunt), and the joyful vocals (Delbert McKay and brothers Walford and Delvin Tyson). All from Southall in West London, although most of the band were born in the Caribbean.

Ironically, it arrived when Roots Reggae was in decline in Jamaica, Dancehall was in the ascendant, and domestic Lovers Rock was the rising sound in UK reggae.

My Tony Peake-sourced copy is still in storage in Auckland (see the opener in this post), but I saw a lovely original (with the first black and white imaged cover) in Bangkok, and I decided I needed a physical copy. Bam.

Fifty years on:

Chicago Underground Duo – Hyperglyph (International Anthem, 2025)

This almost feels like a nostalgic romp through IA's past, from just over a decade ago, when the Chicago label arrived and threw (in the best possible way) astounding concoctions of disassembly, reassembly, dub, music on the fringe of jazz, and much more. This is no surprise, as the duo–Rob Mazurek and Chad Taylor–have not only been doing this for a long time but have also been core figures for the label. They partly define a record label that refuses to be put into a box by continually deconstructing.

The starting point for this record (as it is for so much music since) has to be Bitches Brew, when that extraordinary Davis band took an electric hammer to their genre, so much so that Brian Case in the 1978 Illustrated Encyclopedia Of Jazz facilely stated that after In A Silent Way (his album before BB), “his subsequent work is of little interest to a jazz collector”. I wonder what Brian would make of Hyperglyph as it melds together avant-garde jazz, electronic textures, pan-African influences, early New Orleans and often furious polyrhythms. It’s addictive.

And here’s the much-missed jaimie branch in London in 2017:

Cecil Taylor – Silent Tongues: Live At Montreux ‘74 (Freedom, 1975)

Solo piano at Montreux by one of my heroes. However, until I saw this in a bin in Bangkok a few weeks ago, I had no idea it existed, such is the breadth of CT’s vast catalogue, and solo piano from a pianist who joyously battered his keyboard was very unlikely to trouble middle 1970s NZ, where Keith Jarrett was the definition of jazz piano on the edge.

Scott Yanow on AllMusic describes it as “thunderous” and “otherworldly,” which seems understated, as Taylor relentlessly explores and often passionately advances through 70 years of American jazz and anger, dragging it all into the mid-70s avant-garde. A remarkable record.

Named Downbeat’s Record of The Year in 1975. If only they’d always been so adventurous.

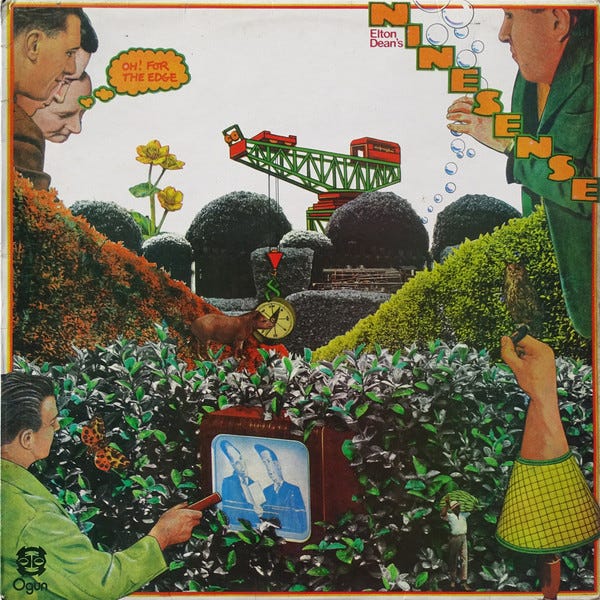

Elton Dean’s Ninesense – Oh! For The Edge (Ogun, 1976)

Elton Dean (alto sax), Alan Skidmore (tenor sax), Harry Beckett (trumpet), Keith Tippett (piano), Mark Charig (trumpet), Nick Evans, Radu Malfatti (trombone), Harry Miller (bass), and the mighty Louis Moholo-Moholo (drums) is an era-defining UK meets South African jazz lineup. Add to that a wild, often melodically expansive live session at the 100 Club in early 1976, and you have an idea what this furnace of creativity sounded like. As punk and as fiery as anything else playing the 100 Club around that time.

The Brazilian corner

Rogério Duprat – A Banda Tropicalista Do Duprat (Philips, 1968) I think I was about 13 when Mum decided to buy me a record and arrived home with The Cowsills In Concert. What could I say? Thanks, Mum. I put on a brave face and an even braver ear, playing it after school over the next few weeks, usually just once before I switched to With The Beatles or The La De Da’s. The problem with The Cowsills was twofold. Firstly, it was a concoction of hits of the day performed, shall we say *slightly*, by the family from Rhode Island who provided a template for The Partridge Family. ‘Good Vibrations’ and ‘The Sunshine Of Your Love’ both struggled with cheery family choruses and vibes, made worse by the fact I had the originals on 45s. But, worse than that, it didn’t have the septet’s only good–no, make that great–song, ‘The Rain, The Park And Other Things’. The perfect fey-psychedelia-for-kids Central Park tune.

When YouTube arrived, I was briefly addicted to the youngest Cowsill, Susan, now a late middle-aged singer-songwriter, performing that song at her usually intimate gigs around the USA. The channel was filled with them (if you go looking), and each showed an audience gleefully reacting to her playing with them with the “I knew, I knew, I knew…” That brief moment passed (okay, I still do the odd search and smile slightly).

Then I discovered Rogério Duprat. Or at least, my friend Chris Bourke sent me a list of late-‘60s and early-‘70s Brazilian pop I needed to listen to. It included some of the obvious names (Milton, Jorge, and Gil, of course), but at least half was new or unheard to me. The name Rogério Duprat stood out.

Naivety and a mental block contributed to that. As I’ve mentioned before, I deliberately kept Brazilian popular music at arm’s length over the years because I was terrified of what it might do to me, of how it would draw me in. The exception was Milton Nascimento, who I came to via Wayne Shorter, but even then, I only had a couple of solo records. (This is fantastic:)

All I knew about Rogério was his reputation as an arranger and orchestrator. He was, it was said, known in his homeland as the “George Martin of Tropicalia” and the “Brian Wilson of Brazil”.

The record listed on Chris’s list was 1968’s A Banda Tropicalista Do Duprat, which was described as “like one of those easy listening big bands from the ’60s was washed in acid and woke up in the middle of the rainforest.”

Want.

And he’d remade ‘The Rain, The Park And Other Things’!

I did the YouTube thing and discovered a wonderfully warped remake of what was then a huge hit, The Beatles ‘Lady Madonna’:

I mean, listen to the drum clatter, the vocal, but mostly the insane chaos of the middle eight, which arrives at 58 seconds. I assume that’s Os Mutantes’ guitarist Sergio Dias on tape-induced speed?

The original 1968 album will, it seems, set you back around $800, and it’s literally not been on vinyl since. Or, at least, legally. I found a copy in Bangkok, brand new, on one of those seemingly endless Russian reissue labels, Lilith, lovingly packaged and sounding rather good, but a bootleg nonetheless. Released in August this year, it’s the first time on black wax since 1968. It was $30.00. A win for everyone (except the songwriters, Rogério’s heirs and Universal), but I bought it. How could I not?

It was a lush orchestral blend of madcap, wild, and intriguing, full of covers, one of which was [drum roll] ‘The Rain, The Park And Other Things’. Writer Charles Peronne’s definitive Masters of Contemporary Brazilian Song, oddly, given his credits, mentions Rogério only once, as a co-composer with Gilberto Gil. So I did what you do and turned to Google. Wiki provided a better but still somewhat stilted biography (MPB is very poorly covered by Wiki, and I doubt Elon’s Christo-fascist white-boi replacement will serve us any better). That he studied in Europe with Stockhausen and Boulez and then employed those talents to push the limits of Brazilian pop, AND thought ‘Revolution No.9’ was one of Lennon’s masterstrokes, AND loved Yoko’s records, works for me.

The album is eccentric, but it’s an often luxuriant eccentricity that blends contemporary Anglo-sphere pop with tropicália, and the wild twists are addictive.

The sleek instrumental version of Caetano Veloso’s beautifully cynical ‘Baby’ is gorgeous, and predates the famed Gal Costa version by a year or so, I think.

Ok, that’s maybe a little nutty too.

Here’s the Cowsills cover, and that’s happily oddball too.1

And as a blog-bonus, a fab ‘Baby’ by Gal, from 1978.

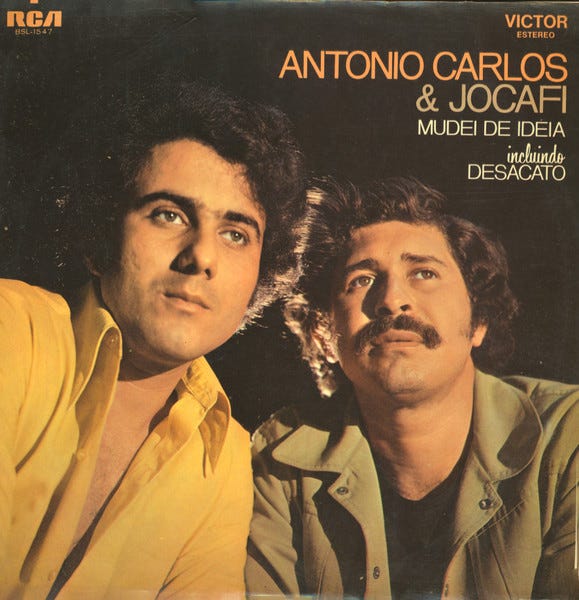

Antonio Carlos & Jocafi – Mudei De Ideia (RCA Victor, 1971)

I found Antonio Carlos & Jocafi’s Mudei De Ideia in a shop in Lisbon, and it just looked interesting. The sticker said: Peter & Gordon on drugs. It was hard to resist that pitch, and it was only $25 or so, and, yeah, it’s cool. I’m not sure if Peter & Gordon ever discovered acid (although Peter famously discovered James Taylor and went on to produce and A&R extremely vapid West Coast pop-rock that spoke of excessive weed and coke in the 1970s), but they never made records like this.

Tripped out Brazilian fuzz-funk and psychedelic rock wrapped around lovely melodies, all arranged by the aforementioned Rogério Duprat. Check out the last minute of this monster:

It comes with two sleeves, one being a more marketing-friendly psychedelic design, with flared reds and yellows, and the other, the original, which, yes, makes the pair look a little like a Latin Peter & Gordon. Mine is the Peter & Gordon version, and I much prefer it.

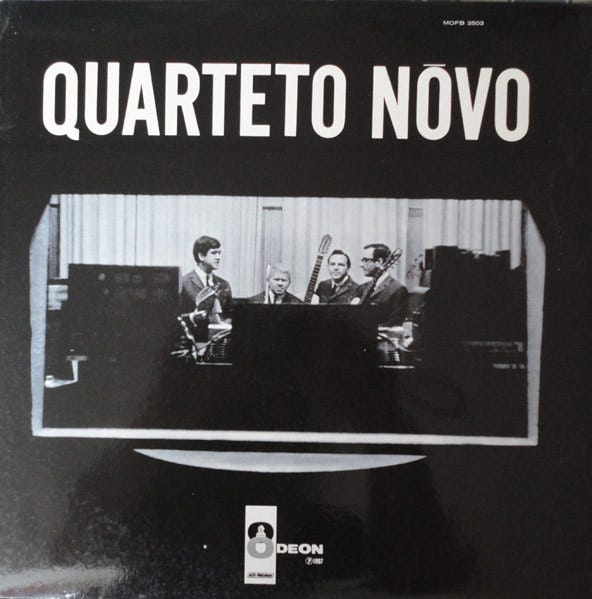

Quarteto Novo (Odeon, 1967)

I’d long known about this, mainly because of the involvement of the late Hermeto Pascoal, but I had never seen a copy. Nor is it streamed anywhere, apart from YouTube, presumably due to copyright restrictions. Then, late 2024 saw a very limited, apparently official release on the new Jazzybelle label, founded by respected French music businessman Olivier Rosset. Still not streaming anywhere, including Bandcamp. Odd.

While I don’t have that, around the same time the reissue arrived, I found an older legit Brazilian copy (2003, the previous legal issue) from a friendly local global music shop here in Bangkok, on the original Odeon label, which works for me, and it’s in perfect nick, both the sleeve and the black plastic.

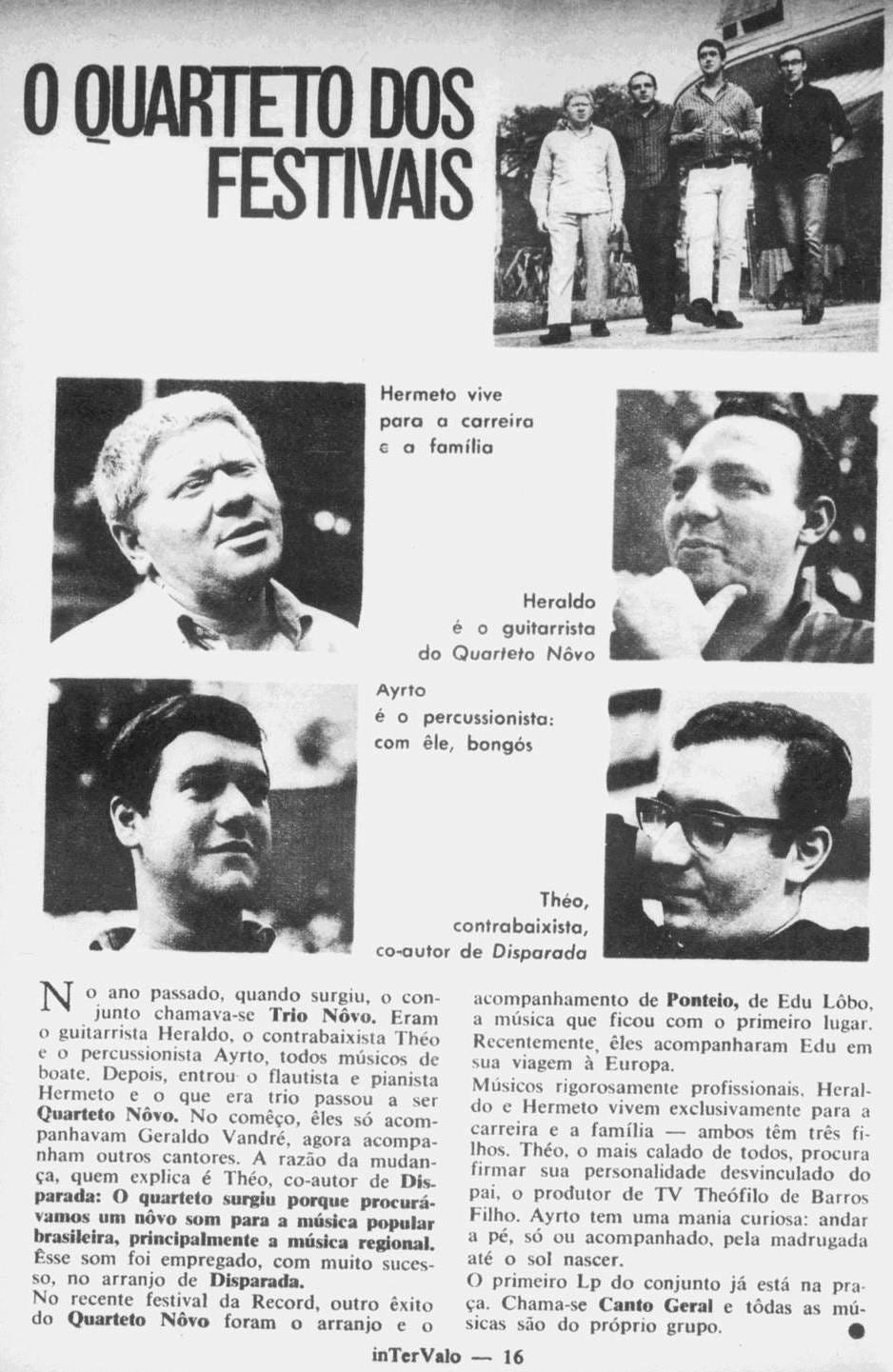

So, music from North East Brazil, created by legendary percussionist Airto Moreira, bassist and guitarist Theo de Barros, guitarist Heraldo do Monte, and later, but in time for this, the band’s only album, multi-instrumentalist Pascoal. The story goes that the band spent a whole year in rehearsal before recording this. And then Hermeto arrived, and Trio Novo became Quarteto Novo.

Luis do Monte, Heraldo’s son, was quoted as saying that the idea was to use the rehearsals as a laboratory in search of a distinctly Brazilian “formula” for improvising and composing.

If I’m honest here, I’m very much out of my comfort zone here. Not only is my understanding of the nation’s music still in the early stages of a personal work in progress, but I’m also hopeless at musical terminology when it involves things like tuning and scales. Yet, I also recognise when sounds seem revolutionary, even in hindsight. I know that the first Beatles albums upended the way we create and listen to popular music, and I understand that A Love Supreme and James Brown’s Live At The Apollo did the same in their own ways. Revolutionary records.

However, I’m more reliant on the words of others because I don’t have a grasp of the context. So, when writer Thom Jurek tells me that this record blends the time signatures and tunings of Brazilian baião with the players’ obsession with American bebop, creating something that sounds so unique to my ears, I need to trust him.

This meld of styles and the deep interest in subtle yet innovative rhythmic interplay, counterpoint, and taut song structures are to this day quite revolutionary.

Despite my naively cloth ears, even I can hear why this mattered, why it adjusted the fulcrum a little and why other people both swooned and borrowed from it.

To be honest, I’m adverse to the flute. It’s probably something to do with girlfriends dragging me to truly dreadful Jethro Tull gigs in the early 1970s. My first reaction to the opening track, ‘O Ôvo’, was exactly that. However, the passion eventually won me over, and by the time we reached ‘Fica Mal Com Deus’, with its hint of where Elton may have borrowed the verse melody for ‘Rocket Man’, I was as captivated as Burt Bacharach was when he openly acknowledged a debt to this album.

After this album, there was no more. Airto fell out with Hermeto and moved to stardom in the USA.

Totally addictive.

Hermeto:

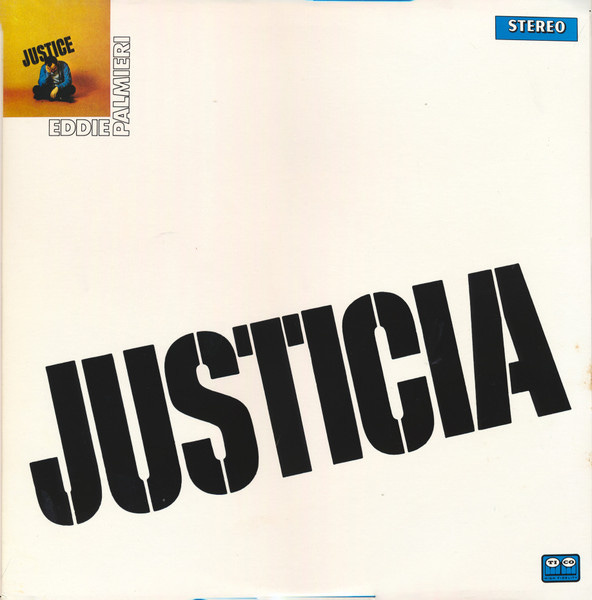

Eddie Palmieri – Justicia (Tico, 1969)

When Eddie passed away recently, Justicia made the NYT list of 13 Essential Songs and Albums, saying of the title track, “Ismael Quintana’s plaintive vocals set off a firestorm of a chorus section, with Palmieri battling with percussion and trombones.”

Yeah, exactly.

As the title suggests, this is an album of protest and injustice, but almost all the lyrics, on the tracks that have them, are in Spanish, which means I mainly need to relate to the music. The one exception is the first track on side two, ‘Everything Is Everything’, which Eddie sings in English. That’s a fantastic groove, but the words are somewhat slight, and indeed, the one repeated criticism of this album concerns that lyric. However, ‘Everything…’ really serves as an interlude between the two most striking tracks on this record, a necessary breather (I’ll get there).

The first side soars, and the English translation of the gorgeous ‘Armour Ciego’ suggests Justicia is not solely about injustice and anger. Still, the final track, the instrumental ‘My Spiritual Indian’, abruptly shifts pace. It’s angry and visceral in the way it combines an almost modal, percussive, experimental piano, as he fiercely confronts the keyboard. He’s surrounded by a semi-psychedelic guitar (Bob Bianco), punching brass and percussion that add layers and elevate the record far beyond the melodies of the earlier tracks. It needs ‘Everything Is Everything’ afterwards to ease the tension; however, that leads into another fiery tour de force, the final track, ‘Verdict on Judge Street’, which runs over eleven minutes. Well, not quite the finale–it is bookended by 23 seconds and then 2.38 of Bernstein’s ‘Somewhere’, as if to offer some final optimism. In between, Eddie’s keyboard is relentless, battling David Hersher Lawrence Evans on bass and Robert Thomas on drums from the six-minute mark, as if they’re all trying to break down a wall. It’s extraordinary before it segues into “There’s a place for us, somewhere… “

Oddly, the streaming version has dropped ‘Somewhere’. Rights, maybe, or maybe the optimism has simply faded. Eddie oversaw the digital reissue. Here’s a playlist that includes it, but ‘Somewhere’ has been fully moved before ‘Verdict’.

John Cale – Academy In Peril (Reprise, 1972)

John’s third post-Velvets release and an entirely different record to the one that came before (Church Of Anthrax with Terry Riley and all that implies), and after (Paris 1919, arguably, and I would do so, his masterpiece). Except it’s not, is it? At least, it’s very much the record that took us to Paris 1919.

Americans appeared quite confused by it, and the reviews were generously mixed. Sales were even more uneven, and, remarkably, Warner Bros. funded another release, but this was during the Mo Ostin era when art trumped sales, and this was John indulging his art, with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on two tracks and an extremely costly die-cut Andy Warhol sleeve. Rolling Stone described it as a classical indulgence, but it’s not; it’s Cale indulging his gothic impulses, his playful faux orchestral arrangements, his influences from lounge to calypso to electronica (long before the term was coined), his Welsh humour, his love of pastiche, his nostalgia, and the theatrical. The title reveals this.

It’s a very unserious record, one I bought as a teenager and fell in love with immediately, despite the fact that EMI in New Zealand had decided the cutout sleeve was far too expensive; therefore, it went the same way as Sgt. Pepper in Aotearoa, although with a gatefold, unlike the Psychedelic Fab Four, which had the gatefold, inner sleeve, and insert all removed by a cash-conscious record company. I mean, what did The Beatles sell? (We finally got it in the late 1980s when EMI NZ stopped pressing in Wellington and all vinyl was imported.)

Considering it probably never sold more than the initial pressing of 500 in NZ (Cale, that is, not Pepper), it was likely a wise decision, fiscally, if not artistically.

What it did mean, though, was that I (and the other 499 who bought it) were primed for Paris 1919, which is essentially The Academy in Peril with vocals and lyrical drama.

A wonderful, wonderful record, and I play my copy (now with the proper Warhol sleeve) all the time – still.

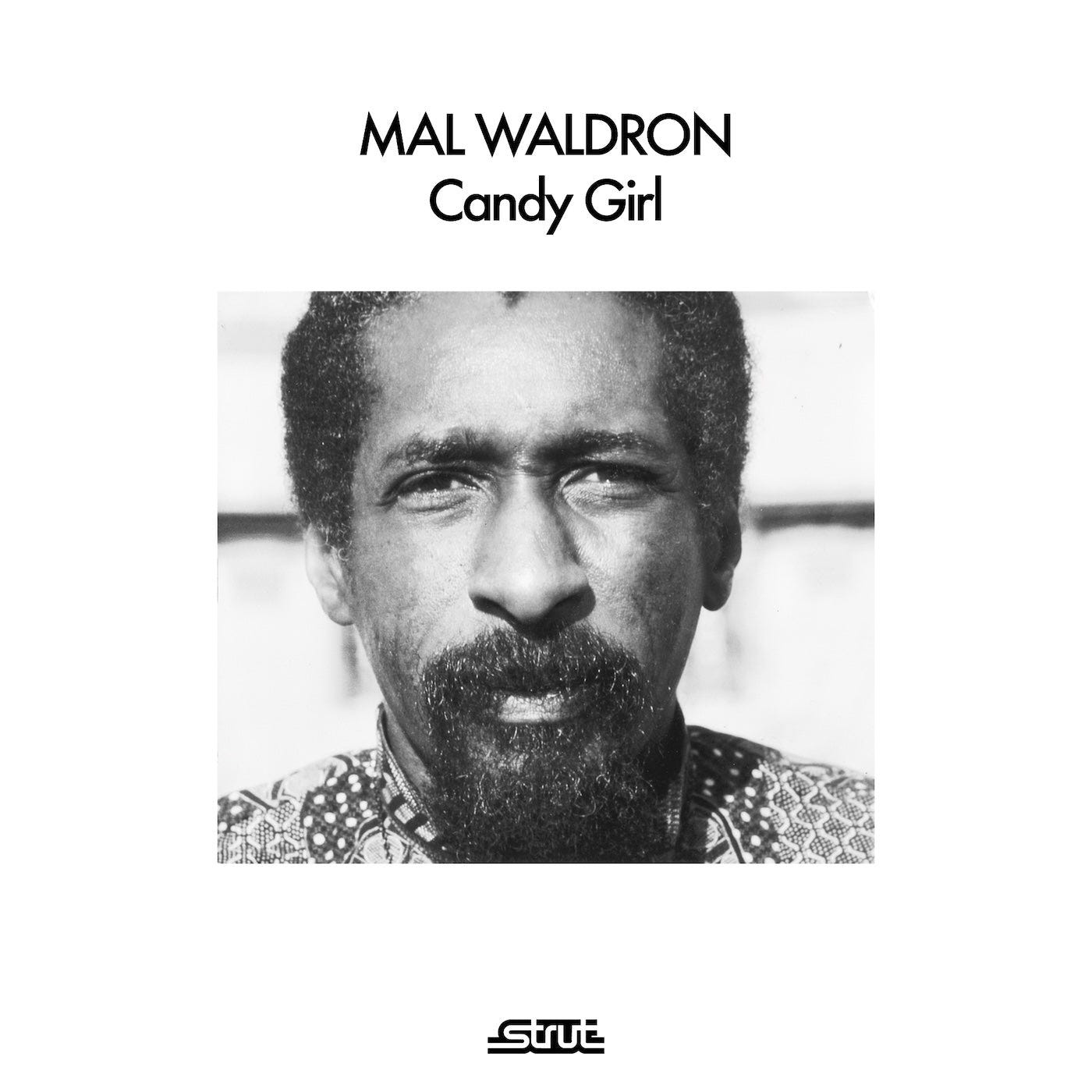

Mal Waldron - Candy Girl (Strut, 1976, 2025)

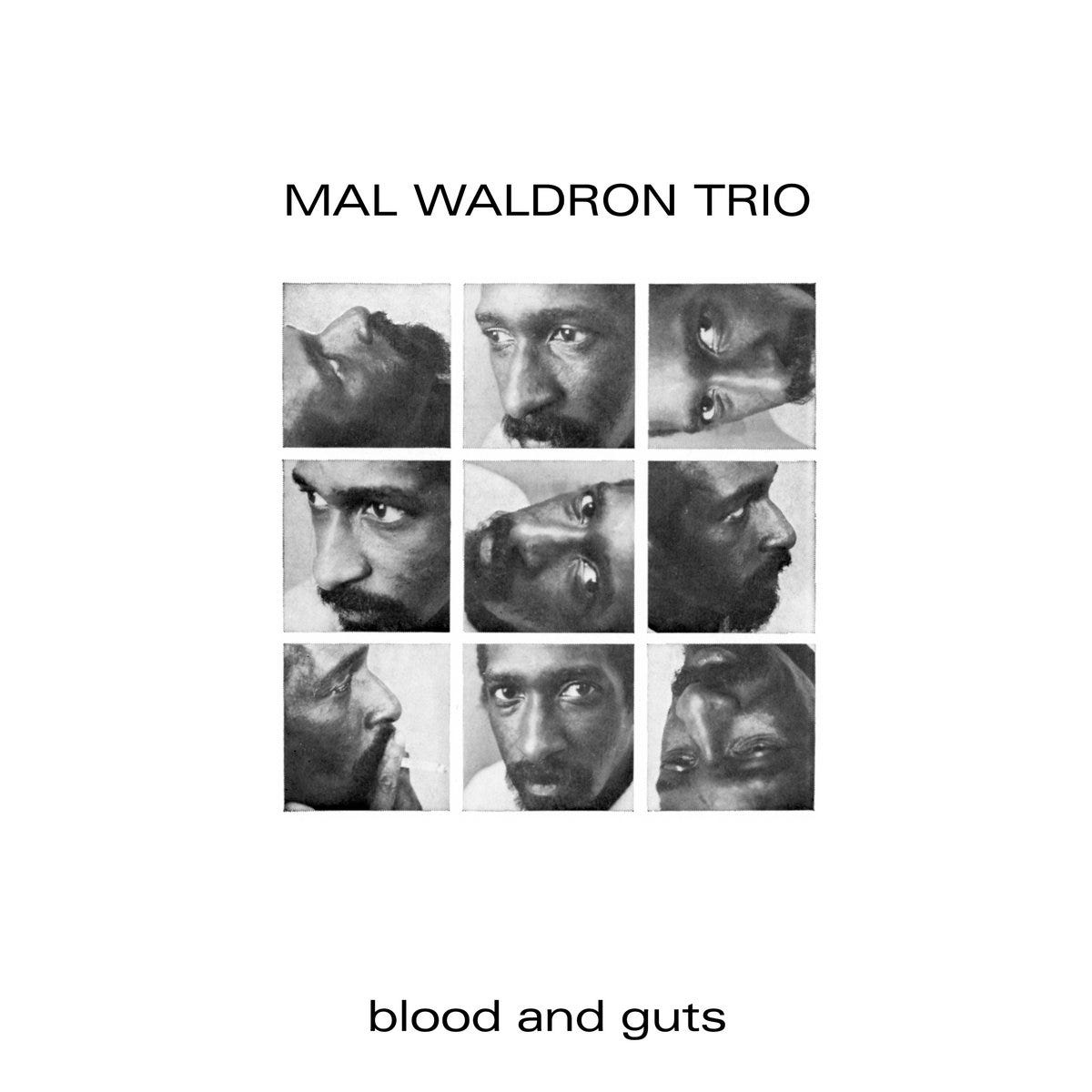

Mal Waldron Trio - Blood And Guts (Phenix 1970)

Mal Waldron played with much of the jazz world, and many times, across six decades. Amongst this, he was Billie Holiday’s regular pianist during her final decade. He recorded over 100 albums under his own name, an almost unmatched achievement.

And I know almost none of them. He was a superstar in Europe, but for some bizarre reason, I’ve always associated his name with a vision of a chubby besuited guy with a conservative lean, which is nuts. He played with Miles, with Coltrane, with Roach, with Mingus, with Dolphy … and with Billie. And it was Billie who made me realise how crazy I was. He's responsible for the sublime piano on Billie’s final album, the exquisite and now critically rehabilitated Lady In Satin from 1958. I was reminded of that when I read Paul Alexander’s terrific Bitter Crop: The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday’s Last Year, which I wrote about here.

I asked two people whose opinions matter to me what I should be listening to, and both said they knew the name but couldn’t recommend anything. I’m extraordinarily wary of AllMusic, and my usual first port of call, the 1986 Rolling Stone Jazz Record Guide, didn’t have any entry, whilst the much patchier Penguin Guide To Jazz Records was dismissive and listed half a dozen records with a snobbish tone. So, I did what you do and took a chance on two records.

The first was the recent Strut reissue of his 1975 lost album Candy Girl, recorded in Paris in 1975 with the famed Lafayette Afro Rock Band. It had long been a rare as hell and in demand as a jazz-funk (as in almost purist modal jazz on electric piano, meets a funk rhythm section, not the less attractive and indulgent 70s genre of the same name) rarity. It was everything it promised to be, mesmerising, gritty and deeply soulful, and as Aquarium Drunkard suggests, “the songs explore relentless repetition and intense stasis, forming ruts so deep they become portals to different worlds”. Truly remarkable.

Then I stumbled upon Blood And Guts in a bin in Bangkok, a 1972 Japanese pressing of a 1970 live album (also recorded in Paris at the Centre Culturel Américain on May 12, 1970), which was last released on vinyl (again in Japan) in 1984 and then in very limited quantities. Indeed, the two Japanese editions appear to be the only instances where this has been properly released in this format, complete with an actual sleeve. It’s been on CD a couple of times since then and is now available on streaming services.

With a local French rhythm section (Patrice Caratini on bass and Guy Hayat on drums), it’s a more traditional record than Candy Girl, but Waldron’s piano punches through with attitude and soul. I find myself playing this more and more, mostly side two, which begins with the terrific, churning ‘La Petite Africaine’ (although, as with Justicia above, streaming services mess with the order on the record and place this at the end of side two).

Is it a meisterwerk? No, but it’s great and, more importantly, Mal is no longer a mystery to me, and Candy Girl has a fair claim to its place in the tabernacle of lost jazz albums that urgently needed reissue.

You need to click through on this to see it, but it’s Mal with Billie and it’s fab:

Tom Skinner - Kaleidoscopic Visions (Brownswood/International Anthem, 2025)

I loved the first Tom Skinner solo record on Brownswood/International Anthem, as well as the live EP (which was actually a double LP) that followed. They were almost undefinable, but perhaps percussion-led soundscapes might work. Yussef Dayes does similar things (his brother Kareem plays bass here), as does Makaya McCraven, and it’s become a kind of raison-de-methode of contemporary jazz and soul drummers. Gone are the days when a drummer as bandleader needed to showcase their skills on the kit (which doesn’t mean I love Tony Williams, Art Blakey, Max Roach or Elvin Jones as bandleaders any less), it just means that Skinner, Dayes, McCraven and others have a new freedom to meld the sounds in their head into a more flexible vision. The studio or the sampler are their kit.

God, this is lovely. The opening track, ‘There’s Nothing To Be Scared Of’, gently slips into your consciousness. I’m not sure if it’s a guitar or a synth, splashed with underplayed drum rolls and then a clarinet (Robert Stillman) and sax. It just floats naggingly, setting the scene for the rest of the album, which never overstates. ‘The Maxin’, with Meshell Ndegeocello, almost vibrates as it slowly awakens, again with understated drums and brass, but despite its 10 minutes, it never overstays. There’s a gentle shimmer as it rises and falls repeatedly.

Is Kaleidoscopic Visions jazz? Who knows, but what’s jazz? Who knows? Which is how we end up with records like this.

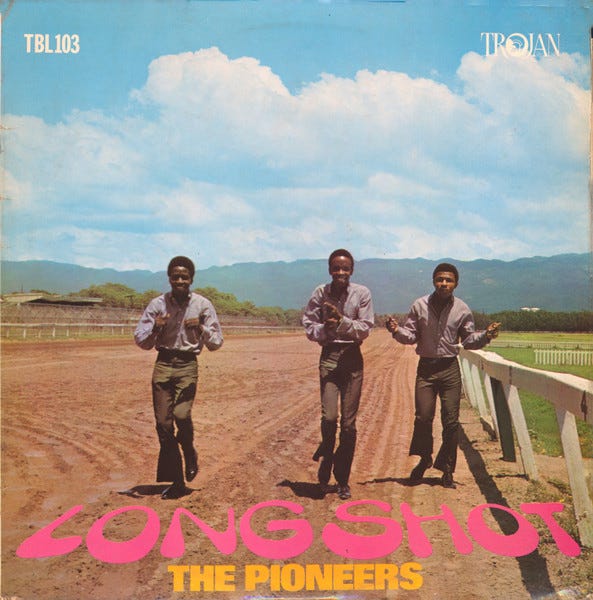

The Pioneers – Long Shot (Trojan, 1969)

This is a journey:

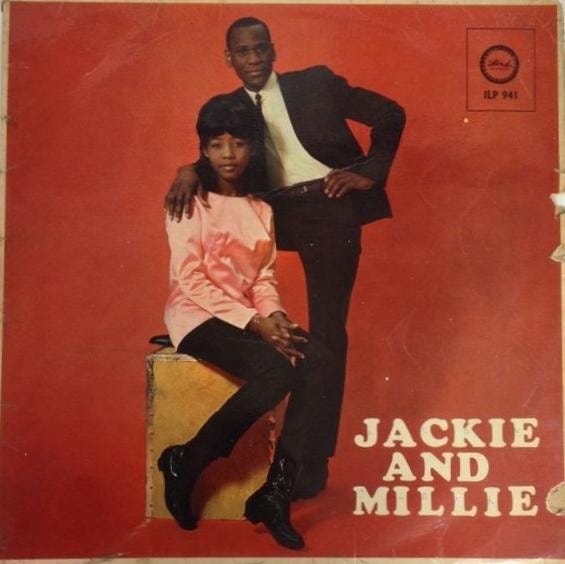

New Zealand around 1980 was a sponge — not just musically but culturally. We were slavishly behind the UK in particular (the USA would come later) and that year we discovered ska and rock steady in a big way. Aotearoa was not oblivious to these sounds earlier, of course. Jackie Edwards was probably bigger in NZ than anywhere outside the UK and the Caribbean, and there was a time when every second act wanted to Do The Bluebeat, but that was more to do with Millie Small than a real passion for all things Jamaican. Jackie and Millie toured Aotearoa in the mid-60s, and it’s notable that Jackie’s lovely 1966 album Come On Home only saw release in the UK, Jamaica, Canada … and New Zealand. As did the Jackie & Millie album, Pledging My Love.

Desmond Dekker’s ‘The Israelites’ was also a Top 10 hit in 1969. Local indie (owned in NZ by a cinema chain and Rupert Murdoch) Festival Records, with its license for both Island Records and Trojan Records, with its countless subsidiary labels, released quite a few of the Jamaican 45s that were crossing over into the UK pop charts at the time. Starved of any airplay (maybe a nighttime spin for Jimmy Cliff on Hauraki), it was usually just token releases with no chart action.

Albums were even rarer. Festival released the 1970 Dave And Ansel Collins’ Double Barrel album and a Jimmy Cliff album at the same time. That was about it until Festival Records rolled out the soundtrack to The Harder They Come sometime in 1973. It wasn’t until 1974 that we had albums (via Festival) by Marley, but not by anyone else. 1975 saw Virgin’s magnificent Front Line compilation. Then, in 1976, the record companies that controlled what music we were allowed to buy or listen to pushed the gates open a little more, and we were able to hear long-players by Toots, Bunny Wailer, Peter Tosh, Burning Spear, and Jah Lion.

What that brief history tells us, though, is that a record like The Pioneers’ Long Shot, one of the classic albums of the post-ska era as rocksteady evolved into reggae, was not only never released in New Zealand but also not available to hear. Anywhere. An album that contained the UK Top 20 hit ‘Long Shot Kick the Bucket’.

Oddly, Festival released this Pioneers 45 in 1972 or 1973, but that’s the only NZ release by this band, ever.

Fast forward to the end of 1979, and the arrival of the Coventry sound, particularly The Specials, was upending the UK indie scene and, subversively, the pop charts (until Chrysalis gobbled them up, with all that eventually implied). One of the band’s key tunes was a rousing version of ‘Longshot Kick The Bucket’, which featured on their January 1980 UK No.1 live EP Too Much Too Young, released in June that year in NZ, where it reached No.47. A chart position that doesn’t come close to reflecting its omnipresence.

It was pushed to No.47 in Aotearoa by the rapid, almost frenzied adoption of the Coventry sound by teenagers in New Zealand at the time. Back then, it seemed unremarkable: a musical or cultural trend exploded somewhere in the world, in the countries we looked to for cultural guidance (and the UK was very much that then, a generation still called it ‘home’), and the remote outpost jumped on it.

And yet, this time it was remarkable. These culture transfers usually took six months or a year to arrive from ‘home’. We were still deeply into UK rhythm ‘n blues while the distant western world had put flowers in their hair (although we loved the bandwagon jumping hit of it all the way to No.1 in August 1967), and acid fuzz guitar had replaced blues fuzz, primarily because of our distance, our media, and the control of big record companies over access. We discovered glam a year or so late (thanks in large part to Pye/RCA doing the bare minimum to promote Bowie until RCA UK stirred up fuss in 1974), and punk only crossed over from a tiny, excited handful some 14 months after the whole of middle UK was horrified by snotty, swearing, drunk kids abusing TV presenters.

But the second coming of ska arrived almost immediately after the Special AKA slammed into the UK charts in August 1979. Within a month or two, every band on Auckland’s North Shore was adding a Prince Buster or Skatalites tune to their repertoire of Clash and Monkees covers, and by the end of the year, the inner city’s youth was clad in black and white. Pork pie hats would be one of the tribal identifiers of early 1980, that is, until we either new-romaticised or angular post-punked as the year progressed. By mid-year, ‘Long Shot Kick the Bucket’ was an anthem. You heard it at parties and on stages. However, not the Pioneers’ version, which remained a mystery to most.

The song that had been a skinhead urban anthem in the UK at the start of the 70s had become a teenage urban anthem on the other side of the planet a decade later.

But what had changed? Why did the usual year or more delay in cultural transfer to the antipodes shrink to a month or two, almost overnight?

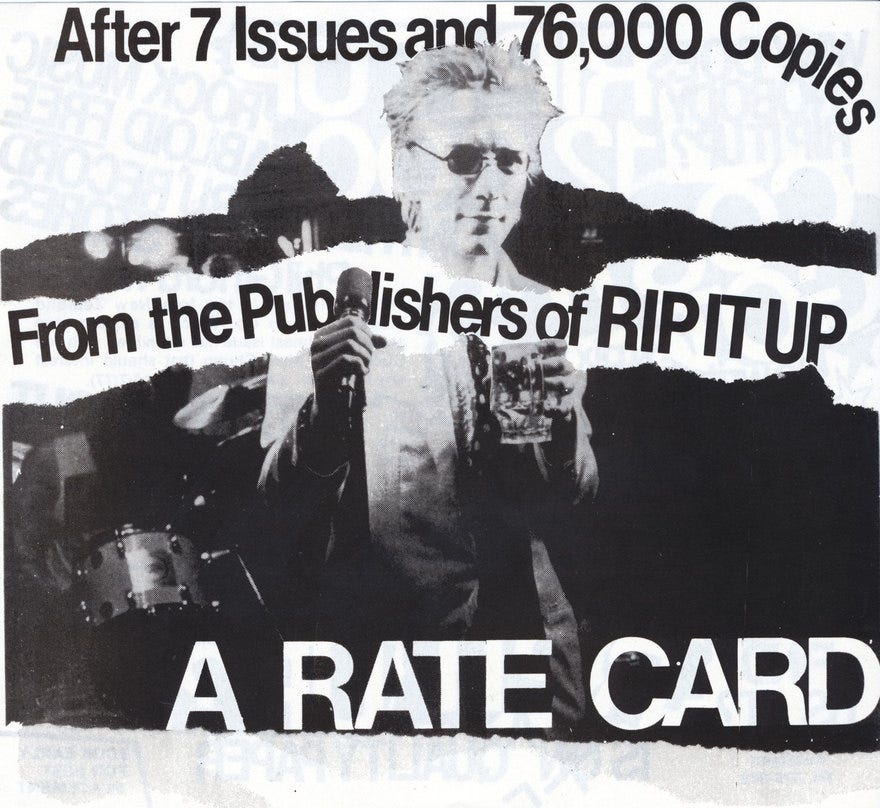

Three words: Rip it Up. Murray Cammick and Alastair Dougal launched their monthly music magazine in June 1977 with 10,000 free copies distributed nationwide, but it wasn’t until 1978 that Murray’s (it was his by then) magazine began to reach critical mass and noticeably influence the music we were listening to, how soon we listened to it, and, eventually, the music we were making. That it coincided with punk and the music that followed was fortuitous for both the music and the magazine. Punk and then indie gave RIU something to hang its hat on, and RIU provided a source to know about it all without waiting months, and a place to celebrate it in words (the brief Rip It Up Extra added terrific images). We’d never had that before. The earlier Hot Licks, as fine as it was, had little in the way of international news, relying on the whims of local record companies and following their lead.

Rip It Up reversed that and was supported by two smaller record companies eager for new product, RTC with its Virgin labels and Festival, driven by a new, younger team and a catalogue that included things like The Specials’ neat 2-Tone label and Chris Blackwell’s forever edgy Island, which was actively signing acts such as The Slits, Ultravox, and Steel Pulse, along with a vast amount of reggae, Grace Jones and a ton more. Across at WEA, Terry Hogan (who would soon push the label into signing Toy Love) pressured the company to release similarly edgy records. RIU also created a sense of momentum and symbiosis with a soon-to-be revitalised Radio With Pictures and broadcaster Barry Jenkin’s go-to late-night shows.

All of this coalesced into a public voice demanding that releases not only happen in New Zealand much earlier than the usual six to 18 months after the international release, which was the norm, if at all sometimes. Public noise forced PolyGram to release The Jam, reissue Velvet Underground and Nico records, and much more.

If you want to read Rip It Up to see exactly why that was, try the first couple of years here. We knew, and Murray was the reason. We never looked back, and after import licensing was relaxed in 1982, the floodgates opened.

But to the record at hand. I was one of the then three million New Zealanders who had no easy access to the original single or album by The Pioneers in the 1970s or early 1980s. The first release of the original track seems to be the Music World release of the classic 1969 Trojan compilation Tighten Up Volume 2 in August 1982 (yes, Rip It Up tells me that too).

However, the album was out of print in any form from 1980 to 2010, probably due to Trojan’s legal quagmire when Universal finally released it on a budget CD, and I bought it in Singapore, of all places. I fell in love with it—the glorious, sparkling but gritty Leslie Kong production of a dozen infectious stompers that paved the way for the global reggae explosion of the next decade (without the pioneering Kong, who died in 1971), and, yes, 2-Tone and eventually ska kids in Auckland, New Zealand.

But I’d never owned or even seen the original 1969 orange and white labelled UK vinyl (originally released for £1) until April, when I spotted it in Paris. And pounced.

Reasons to be cheerful, part 3

Two books

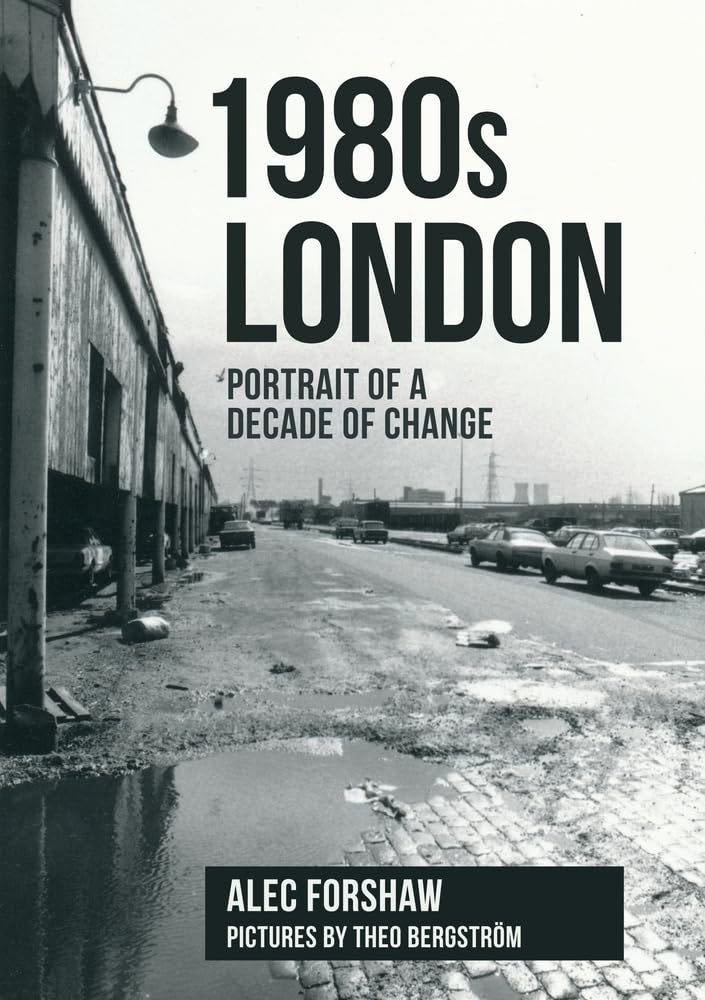

1980s London – Alec Forshaw (text), Theo Bergström (images) (Amerley, 2021)

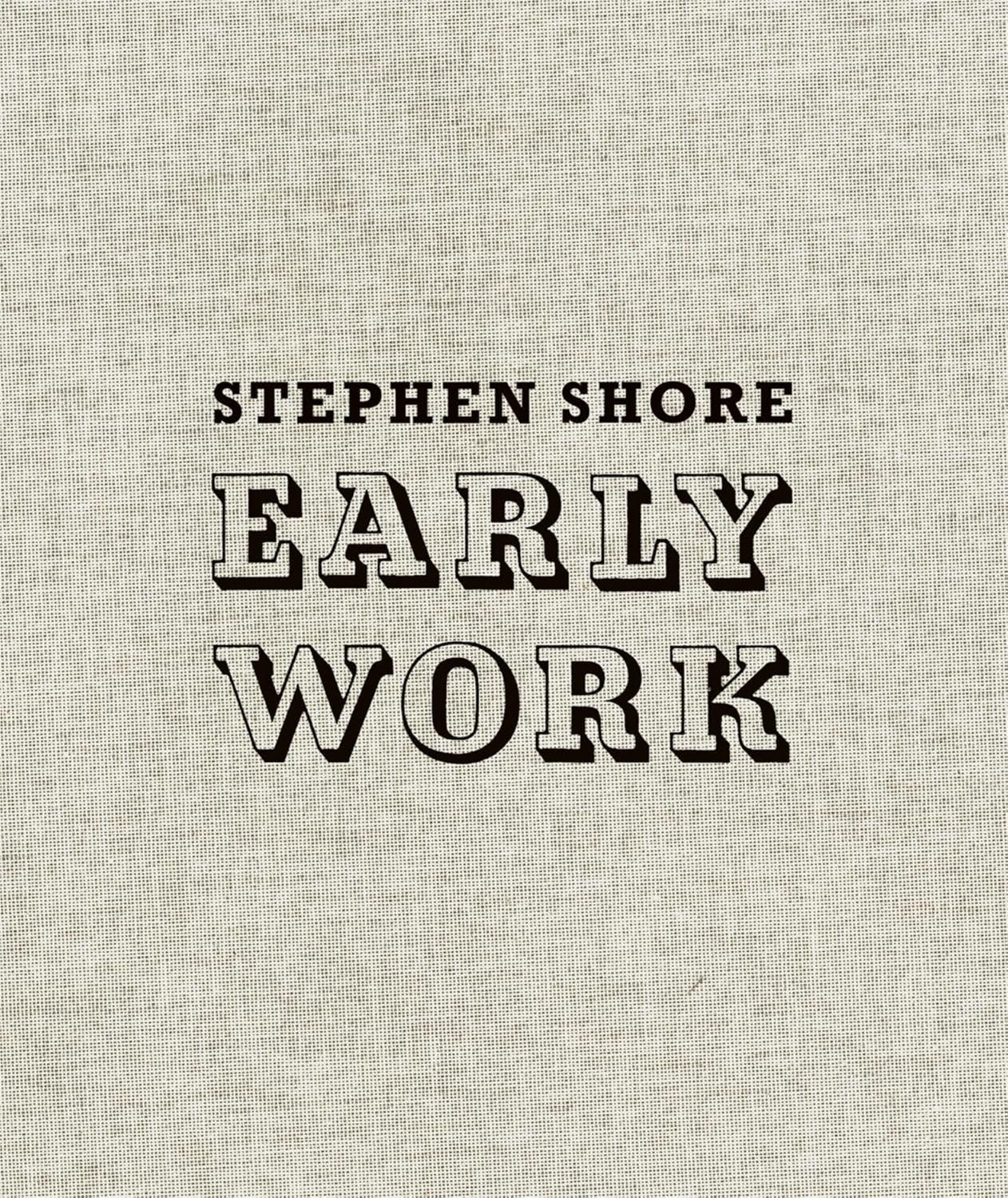

Early Works – Stephen Shore (MACK, 2025)

I’m addicted to photography. It’s an addiction that manifests in many ways. First, I carry a camera everywhere and constantly think about shapes, shadows, and how a scene might become an image. I bore people by talking about it; secondly, I subscribe to half a dozen equally obsessive photographic YouTube channels (the number fluctuates as I discover new ones, binge-watch them compulsively until they bore me, then move on), and finally, I buy books. There are too many on our shelves, mostly old, but not all. I seek out quirky, interesting books in secondhand bookshops—and I do find them. My addiction also relates to the clutter problem I mentioned at the start of this post. It’s mainly about black and white photography, but with certain limits: I struggle with books filled with endless negative-space street photography (the mostly black images with a lit corner featuring a dark, moody figure is very common and often dull unless there’s a story behind it, although we’ve all been there). (Unless it’s Fan Ho, of course, or Daido.)

Street photography shouldn’t aim to be great art; it should simply aim to tell a story, even if that story is obscure or fleeting. It doesn’t need to follow strict compositional rules or specific exposure parameters. The story is paramount, outweighs all, and can be as straightforward as ‘this person lives on this street’ or ‘this is the street where people like this exist or pass’. Or it can be far more complex. That’s why I was so irritated by the Israeli expat photographer Gil Kreslavsky’s self-righteous post, Your 'Street Photography' Might Not Be Street Photography, in which he explained what street photography is and isn’t. Apparently, when a subject notices you, it can no longer be called street photography. I found Kreslavsky’s YouTube channel extremely helpful for basic techniques, but I’ll pass on nonsense like that.

Street photography captures life on the street. That’s it, which is why I liked these two books so much. I found 1980s London in a secondhand store in Paris; it looked charming, but the era resonates with me. I lived in London for part of that decade—through strikes, riots, Thatcher, an endless onslaught of fantastic life-changing music, pirate radio, the massive changes (for the better) that the Windrush generation brought, post-punk, Ken Livingstone, Paul Smith, Lovers Rock, Julien Temple, New Romantics and club culture, unemployment, The Face, Live Aid, Westwood and Martin Amis. All of this happened in an incredibly bleak urban environment, in a city still struggling to physically escape a war that was only a few decades behind (bombed-out parts of the City and the East End were still a thing), one that was still Victorian in so many ways physically.

I bought 1980s London mostly for nostalgia reasons, and I wasn’t disappointed. Forshaw describes himself as a Heritage Historian. I’m not exactly sure what that is, but his words evocatively capture parts of what was then (and may still be, much more so than somewhere like Paris with its ring road), just a collection of small towns joined together uneasily. Forshaw divides the book into these villages and shares stories about each, of markets gone, of urban decay and often ugly renewal, of clashes, poverty, and wealth.

The text describes communities I remember vividly, like Camden Markets before the area was transformed into a major tourist trap, when stalls were covered in grey-market cassettes sold by feral dealers who always seemed to have a scruffy mutt at their feet, or Coldharbour Lane and Atlantic Road, where cars cruised looking for someone to sell them a five-quid block of hash that might be dogshit (really dogshit) with no possible comeback in that cop-free zone. (Smarter people knew you bought it on foot and retreated into The Prince Albert to check your purchase.)

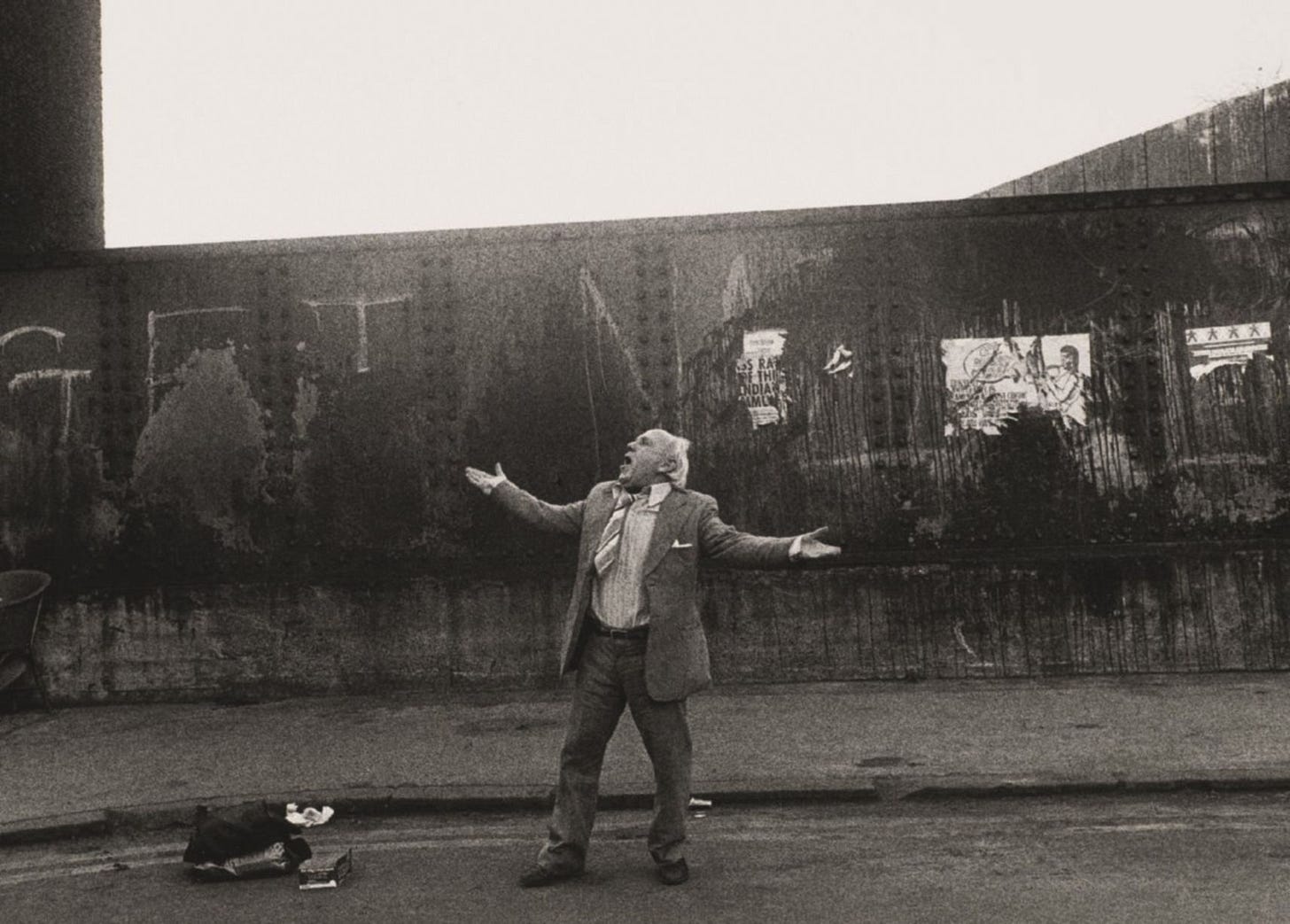

The stories are evocative, but the images are even more so. Theo Bergström is a photographer I know nothing about, and many of the 200 or so photos here probably push the boundaries of technique and the rules of composition, but each page made my soul leap a little; each page spoke to me about a part of my life. Nostalgia, perhaps, but I could almost feel myself watching this one early morning in a Brick Lane that will never exist again.

And I love this Theo Bergström image I found online.

Stephen Shore’s book is quite different. Firstly, he’s famous. But more importantly, his Uncommon Places and its later companion American Surfaces sit easily in the pantheon of great photographic books. Shore initially made his name as the teenager who was invited by Andy Warhol to photograph The Factory and its inhabitants between 1965 and 1968, in monochrome. However, it was his images taken on road trips across the expansive landscapes of middle America and Canada in the early 1970s that elevated him to that pantheon, primarily because they depicted a world of vast ordinaryness in colour at a time when colour wasn’t considered a valid medium. In the 1970s, Shore, Saul Leiter, and William Eggleston forever upended that rule.

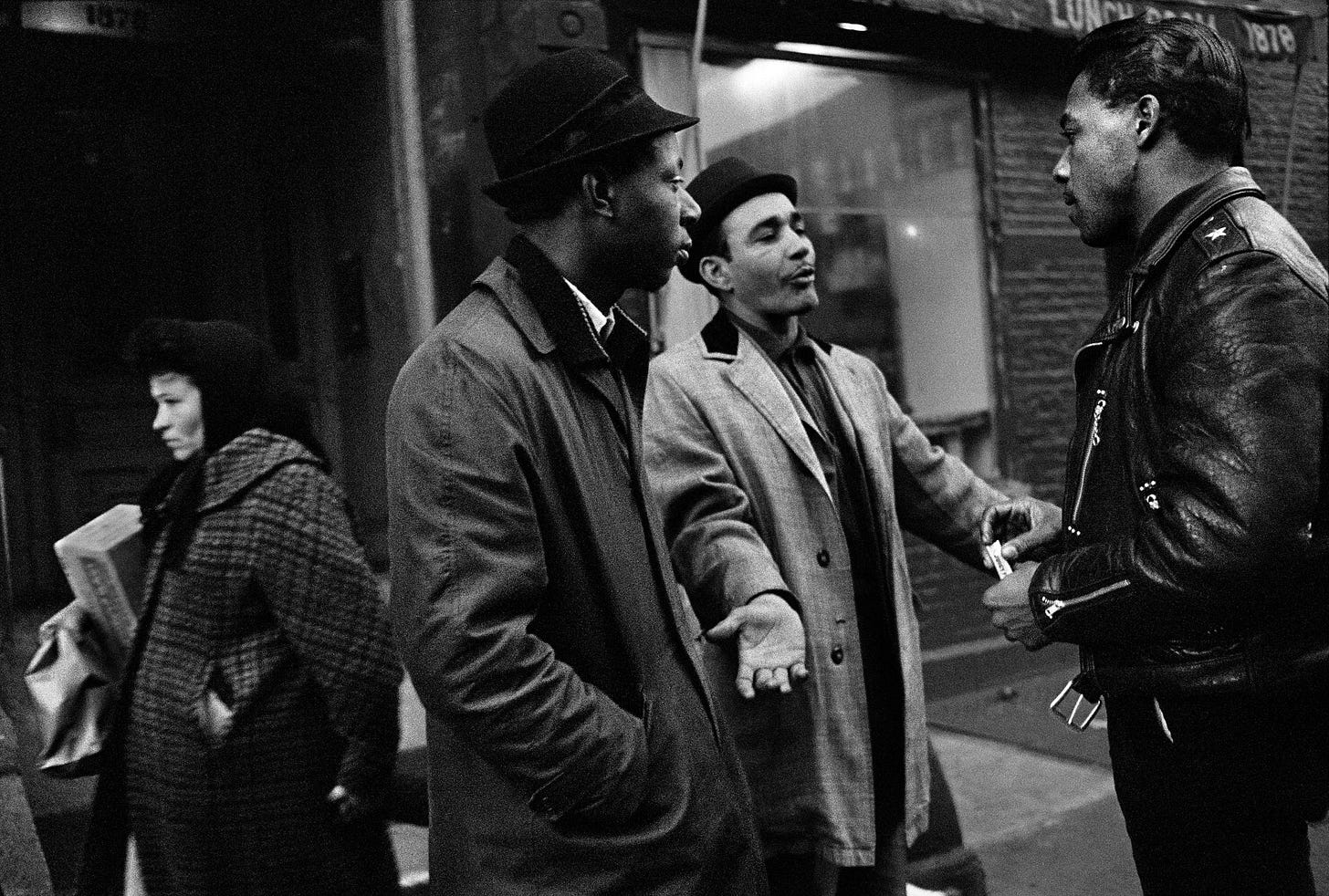

As a ten-year-old, Shore was given a copy of Walker Evans’ American Photographs, which captured and celebrated an American world of ordinary life (not meant negatively) in black and white. It would be fifteen years before Shore would explore that path in colour, but in the meantime, in the years before he met Andy, he was a teenager roaming the streets of New York City, wandering with his Nikon F (which was also my first camera, thank you, Dad), photographing people. Ordinary people doing ordinary things in ordinary places.

I came across a great quote on the internet, in a terrific piece by Irish writer and photographer Alex Sinclair, exploring the origins and impact of Shore’s 1970s widescreen trans-America photography: The thing about photography is that it is impossible to tell which aspects of life today will be interesting to our future selves.

That quote applies equally to these previously unseen images.

They are evocative and wonderful captures of the world the young Shore inhabited and walked through, photographed without text or the need for any further words. They also often break the rules and challenge the earlier claim that street imagery must feature people unaware of being photographed. How can this not be street photography?

Unlike his later, signature 70s work, these images are monochrome and mostly populated by humans as the focal point rather than an adjunct. They’re also deconstructed in a way the later shots are not: elements clash amidst urban chaos and grime. It’s not a city of joy, but it’s a city of interaction, which is all that good street photography really needs to capture.

And Stephen Shore? “I remember none of it! I mean, there are a couple of pictures that I remember taking, but it’s almost like an out-of-body experience.”

The naïveté of the images in this book is both remarkable and simply perfect.

Reasons to be cheerful, part 4

A few videos

Brian Wilson in 2003, channelling Gershwin. Off the just-reissued live album.

The demo from an unknown date:

Elvis Costello’s first interview, 1977

Revisiting that interview in 1989:

A lovely live take of Hoover Factory.

'“It’s not a matter of life and death but what is…”

Cool fact. The song was written by Artie Kornfeld and Steve Duboff, who also wrote The La De Da’s ‘How Is The Air Up There?’, possibly my favourite Kiwi single of the mid-60s and a contender for the most perfect 45 ever from Aotearoa. As an aside, Kornfeld went on to create an obscure festival in 1969, which he called Woodstock.

Very much enjoyed the post, Simon. Joan and I had a similar impulse when we went to Lisbon a couple of times around 2000. We could kind of imagine ourselves living there but for all sorts of reasons it would never have happened. At the time I had the feeling the city was in a pregnant moment between its past and its future. I'm sure it's much changed in the quarter century since. Bought a lovely cassette of Nth African music I heard coming out of a shop off the Restauradores.

I've always loved "Hoover Factory", having previously seen the building in some old encyclopedia article which stayed with me. "It's not a matter of life and death / But what is?"… indeed.

Among his other things, I very much like Mal Waldron's work with Steve Lacy like "Hard Talk" and "One-Upmanship". I'll check out a couple you've mentioned that I'm not familiar with.

All the best with your plans.

Beautifully written Sir. Thank you for helping me also add to my Vinyl collection habit! I have a few of them, notably Mingus at Monterey.